Time has passed on, compañerxs. Genocide. Ethnic cleansing. The thirst for land, water, and territory. This hydra is hurling a storm at us that we might not survive, but we attempt it anyway.

The world in decline. Civilizational crisis. I have not shared stories, or report backs, or analysis as promised. Our hormiguero is slow. We write slowly. We read slowly. We organize our hormiguero slowly. But we move.

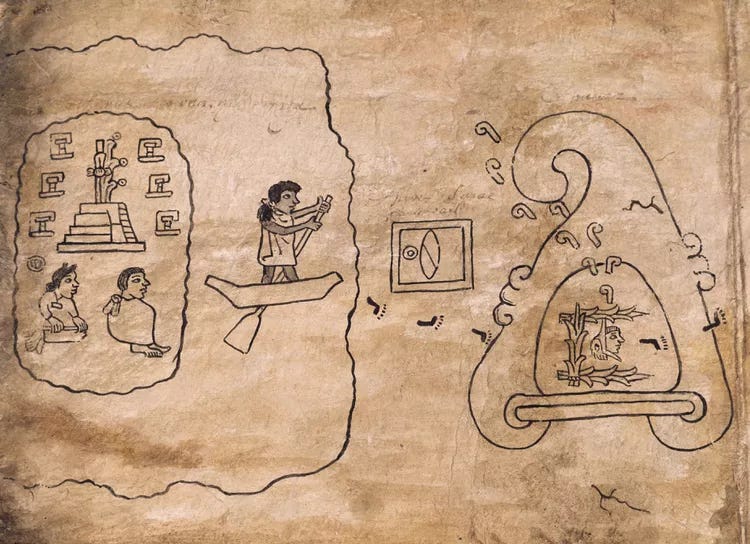

Just six months ago, I had a dream. Our hormiga ancestors gave it to me! I remember, I remember. I wrote down the words quickly to put the image into language. Today, I share that dream as I bore witness to it. Sooner or later, it might appear in a different form, not here but elsewhere. This dream of the future is not a prediction. It is not a premonition. It is simply a story. Foreclosed. Open. Possible. I saw a glimpse of the future hormigueros as a lesson in fiction. Nothing more, nothing less. I ask that you also bear witness with me.

Dear compañerxs, may we not despair in these times of crisis and the next. And if we do, may we despair together. Our cycles of struggle only strengthen us. Las hormigas around our earthmother fight to their last breath. We breathe that fight every day.

A woman wails. Her weeping cuts through the winds, suffocating the air. With her, other women are wailing too. It is a cry, together, in the night, in the valley of mountains. The waters descend from the ancient rocks, soaking up all their tears. They are dressed in black, covering their faces with rebozos. In the distance, a fire erupts.

Silence. The old one speaks. The fire is intense and mad. An old man reaches for a wooden stick resting on the ground and pokes the bonfire, releasing sparks as embers rise from the coal. He surrounds the dignity of the old one. Bodies begin to encircle it, sitting, praying, whispering. The old man hears the tiny laughs muffled by his hands. Despite the long stretches of silence, they can still hear the weeping from the mountains, an echo carrying the density of ancestral noise, the fuzziness of a dry forest at night. The woman is visiting her buried child of seven years. Somewhere in the soil, the earth cries with her. Somewhere in the wind, the earth feels the pain.

The crunch of the burning wood brings attention to the heat, timber radiating in an effervescent, sharp red color. A vital source of life-destroying transformation emerges from this fire. The hormiga elder, Gerardo, steps up to the bonfire to contribute more kindling. Hormiga children’s feet dangle off their seats or are outstretched on the dirt ground, receiving the medicine of fire, the old one kissing their skin. Soft winds blow oxygen into the scorching kindling. It cracks softly as passionate eyes investigate its old, old wisdom. Cedar smoke lifts to the cosmos. Tata Gerardo tosses in a full bundle of white sage into the fire, with a sprinkle of dried tobacco. One might listen to how the smoke communicates, how it tells stories, perhaps rumors, so that we might laugh. It is here that prophecies within raw energy are unleashed. Tata Gerardo sits quietly among children as they fidget and yawn in place, sitting on their logs or blankets.

It has been years since the liberation of Abya Yala, or so the story goes.

For those of us who keep Gregorian count, it is the year 2156. It is the Autumn season. It’s been many moons, many seasons, and many generations since the fall of capitalist civilization, the Storm as we call it. The rebel hormigueros rose, building trincheras across the continent. Some bore arms. Some made the Bad Government obsolete. Some proletarian unions waged class war. Some anarchists led the social revolution, and it all began at home, in our hormigueros. Even in the geographies of Slumil K’ajxemk’op, those lands across the sea, the great hormiga rebellion emerged and persevered. In all lands, the resistance held out. There were no leaders, only people. No egos, only collectives. No vanguards, only assemblies. Some of us remember those times, such as Tata Gerardo’s mother. Yet, most of us know it as a story. “After the Storm,” as the elders tell it, is all we know.

The whereabouts of this gathering are unknown to the children. It is a secret location. Its clandestinity is for protection. It is an isolated, deserted ruin of buildings somewhere in what was known as California, in the land that was once called Los Angeles. We call it what the original people called Tovaangar. The elders call this part Huutnga. It is one of many locations where elders and families are sheltering children.

Tata Gerardo pours blue corn atole for the children. Earlier in the morning, the mothers and elders tended to this nixtamalized corn and made masa. It is a special recipe they made with Hopi corn that they traded beans and chiles for at the last tri-regional tianguis convened in O’odham lands this last season. It is a leftover ceremonial drink from the burying of the child, Antonio. Liberation was not a clean break from the old world. Traces of the ugly persist, its rotten head in the shadows of our lives, lurking and waiting. Antonio suffered this reality, murdered by white ghosts who won’t abandon their myths. His pain and death became our own.

The children sip their hot atole and wait for Tata Gerardo’s words, eager for a story. It has been some time since a story has been told. We are in hiding from the white ghosts. Our hormiguero moves. Some have developed a defense brigade to protect children and elders. They are out there, pushing out the white ghosts, lost in a world of difference. What better way to pass the time than to tell stories?

Tata Gerardo: (Adjusting himself in his seat. He brings a lit match to his pipe with stuffed tobacco. He puffs smoke until the bowl is combusted.) Buenas noches. Good evening, little ones.

The hormiga children stare at the fire and then observe Tata Gerardo. In his old age, he has coffee-stained teeth, a full scraggily beard, and a bald head, noticeably growing new hairs, though he wasn’t balding, just bald. He adorns himself with a brown gaván, with a black colored symbol for maguey etched into the fabric. His boots are dirty and well-worn. The tejana he wears during the day sits on the floor. Dust spins in the light of the fire.

Tata Gerardo: (Looking at the faces before him, pensive.) Today, I will be sharing a forgotten story of our people. I remembered it after all the hormigueros came together in the last week to mourn Antonio. (He remembers Antonio’s lifeless body, bruised, cut, with one bullet hole in his chest. The agony of such an image.) Their travel reminded me of another migration story long ago. This is the story of Aztlan, an hormiguero who rose across what was once called North America. What we call today, Turtle Island. So please, clear your mind and look up to the cosmos, the stars. Empty your thoughts and chistes. Drink your atole to keep warm. Keep your sounds low. When you are ready, look into the fire.

The hormiga children look up. The full moon shines and casts light on the buildings, shadows following trees, cacti, and vegetation. They can all see Venus, bright as a star. The clear skies show a tapestry of stars, moving, still, marvelous, and curious.

Hormiga Giselle: (Fidgeting in her seat.) Tata, is Aztlan a person?

Tata Gerardo: (Letting out a tiny laugh, surprised.) No, mi’jita. Aztlan is not a person. It’s a place without a land. A place of people who put their hands in the soil, in the heart of the sacred. It was a spiritual bond between an oppressed people.

Hormiga Briana: But Tata, how can a place be without a land?

Tata Gerardo: (Shuffling in his seat.) Now, now. Let us not get ahead of ourselves. I will tell the story first. And if the question persists, then ask me again.

The hormiga children sit silently. Waiting. Their curiosity is enormous. For many months and years, they have not had stories told to them. Elders have been sick. They have been occupied with passing down traditions, the old ways, to the new councils of the autonomous territory of Tovaangar. The hormigueros of this trinchera are deciding on a new Council of Elders for the region. It has taken many assemblies, many meetings, many disagreements, and many proposals. Tata Gerardo has been to them all, exhausted from the discussions. He misses the days of semilleros. The work tires him, but he knows it is necessary.

Tata Gerardo: (Taking a deep breath…and releasing it.) Many, many moons ago, before my mother, and her mother’s mother, before the white ghosts who conquered the earth, there were an ancient people who roamed this continent and the planet. They were people who respected the world our great Mother birthed, from the mountains and waters to the four-legged critters and sea relatives to the grasslands and deserts. It was an ancient people who prayed and made ceremony, communicating with this world of abundance. There was a time when people like us could share words with the trees, the deer, the rocks, or the rivers. The people had unique tongues and communed with life. It was a beautiful time. It is the world you know. This was the way of the spirit, as told by our ancestors. It was a beautiful time for these ancient people. But it was also a time of violence. It was a time of balance and equilibrium. (He pauses…) But it was also a time of sacrifice. And as you all know, there was a time when the world could no longer speak. The animals were afraid and dying. Our plants could not speak or share their medicine. For the long night of five hundred years, the world was forgotten. It was the greatest tragedy of our species.

Hormiga Victorino: (Leaning toward Tata Gerardo, raising his hand.) Tata, how can something be beautiful and violent at the same time?

Tata Gerardo: (He sips his atole drink. He looks to the fire and up toward the sky. He turns his head to the mountain, where the woman weeps and the wailing women accompany her.) Victorino, this is a great question. Listen to Mama Teresita, who is praying and weeping for little Antonio, may he rest with the ancestors. (He remembers little Antonio’s gaping mouth, twisted. He could never forget it.) He was found dead only one mile from our hormiguero. The Council of Elders kept this from you all. But listen closely. He was not only found dead but also killed by other people. Murdered by people. Bad people who we have not seen in many seasons. They are from before your time. They found us. White ghosts are what we call them in the stories, and what they are today. They are a band, no more than ten individuals. We think perhaps cannibalistic. Very violent. No purpose in this world other than to hunt nomadic hormigueros or terrorize autonomous territories such as ours. Yet, despite these people, is our hormiguero not beautiful? We live together, eat together, cry together, mourn together, and live our lives to the fullest together, connecting with hormigueros around the world—a beautiful project we invest our time and energy for. (He looks to the fire, and stares intensely.) And in the dark corners of our beauty is our mirror: the white ghosts who instigate destruction everywhere they step their feet on.

Hormiga Victorino: (Curious and afraid, holding his hands between his legs.) But Tata, where have they been all this time?

Tata Gerardo: Mi’jito. I don’t have the answer. The white ghosts live very suspicious lives, on the run, refusing to give up their desire to destroy the life of hormigueros. They were cast out of our assemblies, villages, and lands many, many years ago. This was before building autonomous territories and the assemblies. They have become a hindrance to our way of life, as we were never able to convince them to change their ways. They embraced something else.

Hormiga Gisselle: But if they came back and accepted our principles, would they be welcome?

Tata Gerardo: (Smiling.) You all ask the hard questions. Good. Never stop asking these hard questions. And you know the answer: it is the decision of the assembly.

The hormiga children stare at the embers floating around them, into the sky. A moment of silence passes. A moment of reflection. The hormiga children wonder what these white ghosts look like. How they must smell. What they sound like and what languages they must speak. They know nothing. Nothing other than their capacity and desire to kill. Even a child. Their friend, Antonio.

Tata Gerardo: (Getting his composure right again.) Now, where was I? Oh, right… Okay… As I was saying, Aztlan was of ancient times too, a story of movement across lands, from a land with a bowl of water near a cave within a mountain. This place was almost like paradise, at least in the stories. (He pauses, doubting himself.) The first migration out of Aztlan was into a valley of lands south of us. This valley was located near a lake. The people who were led by a new prophecy built their city on this lake. The lake is still there, and beneath it is the city that came after it. The descendants of this first migration would face the waves of invasion we call the long night. The second migration was a northern journey over many years into a wider scale of lands, which was half of North America at the time. At this point, the Storm was already developed. It had ravaged the land, the people, and our visions. It was with the second migration that Aztlan as a place sacred to some of their ancestors, was lost and then rediscovered as a spiritual bond through the crossing of many territories. Aztlan became a people in search of a new prophecy. Aztlan for these people was a camino.

In the distance, Mama Teresita is still weeping. Her cries by now are guttural with the force of the mountains themselves. With her are mothers from local autonomous governments and neighboring hormigueros. Since yesterday, the autonomous territory has convened in assemblies to address the resurgence of white ghost activities in the region, where multiple bands have been spotted and identified. Clans, barrios, local autonomous governments, and trincheras throughout the territory have sent their representatives to an undisclosed location to discuss the proposal to engage the white ghosts through violence. It was a proposal from Mama Teresita, led by emotions of grief and vengeance. Antonio was the first victim in a long time. He was alone, without a guardian, without someone to watch over him. He was vulnerable, and we failed him. The territory is new to murder in this generation. They called out to other territories for guidance.

Tata Gerardo: (Puffing smoke from his pipe and speaking with it still on his lips.) The first migration out of Aztlan was the beginning of the end. When the ancestors of the white ghosts descended upon these lands of Abya Yala, the Storm erupted. For half a millennium, the Storm grew and grew and raged across the planet. In some territories, the Storm was seen clearly. For others, a simple and comfortable life overshadowed the devastation wrought by the Storm. It was a confusing time for everyone. Not all people understood what it was that caused so much pain.

Hormiga Briana: (Jumping a bit from her seat, a small dust cloud appears beneath her.) But Tata, why is the first migration important? I don’t understand why it matters!

Tata Gerardo: (Happy to hear the question.) The first migration was important because, in the era of the Storm, the free movement of people was assumed as unnatural. Imagine if our friends and relatives of the nomadic hormigueros could not travel across waters, lands, and skies. Imagine if they were stopped everywhere they settled, questioned about their movement, and even asked to leave a territory. Sorry for not clarifying it, Briana. You see, Aztlan was a story that heralded how a people could move from one territory to another, construct a civilization, though not perfect, but without the restrictions of a wall. The story of Aztlan meant that there was a time when people, an entire People, could travel and find home miles from where they were created.

Hormiga Giselle: (Confused by a word, scratching her head.) A wall? What does a wall have to do with a civilization?

Tata Gerardo sits up. He puts his atole drink on the ground next to his tejana, which by now is covered in dust and ash. He places his pipe on a wooden stump. He shifts his body around, trying to find a good position. Habitually, he massages his fingers, one by one. He pulls out a pomada and massages his fingers aggressively. The night cold is intensified by the tiny bouts of wind.

Tata Gerardo: (Taking a deep breath, unsure how to narrate the walls of civilization.) Walls were an artifice of the era of the Storm. But they were not new. Some walls were created to defend lands from invaders, such was the perspective of the old Roman empire who saw barbarians as monsters. These walls were created to keep people out. And these walls, to keep people out, were useful during the Storm for those who sought to restrict the free movement of people, our people. In our era After the Storm, walls were destroyed. Our ancestors of the time sought to rethink our relationship to walls and what they called colonizers. To protect our sacred lands didn’t mean building walls. It meant new relations to the land. They reminded us of a time we no longer desired, walls and all. Now, the walls that do exist are mostly divided between mundane spaces, such as the walls of our homes. A mundane existence.

Hormiga Victorino: (Intrigued and wondering how anyone could be limited by travel.) So… the first migration was a time when anyone could walk anywhere?

Tata Gerardo: That’s right, mi’jito. However, don’t confuse free voyage with welcoming clans or territories. Not everyone shared the practice of wayfaring without consequence. Some nomadic clans and tribes of the old days were limited to their territory. Some traveled distances to find new homes and settled in open lands. Some traveled and enacted violence for their place in a territory. It was a varied experience. Any more questions or curiosities so far?

A few of the hormiga children raise their hands in excitement and blurt out their reactions.

Hormiga Briana: (Yelling with the full force of her lungs, with a rapid succession of words.) My older brother told me that when the white ghosts invaded our lands a long time ago, there were wars between territories, like if we went to war against another hormiguero! That’s why—

Hormiga Victorino: (Cutting his friend off…) —and my uncle said this is why we all look different! Because our ancestors came from different places, with different colors!

Hormiga Giselle: (Talking over her friend…) —but if the first migration teaches us movement, what does the second migration teach?

Tata Gerardo: (Trying to keep track of the noise of voices, he puts his hands up to indicate he’s heard too much, overwhelmed by it all.) Okay, okay, settle down. You see, when the white ghosts founded their civilization through the destruction of the earth, the sacred, and life, the freedom of movement ended. The world changed with the Storm. We changed. This is why the second migration for Aztlan came to introduce a new way of seeing the world. It pierced through the fantasies and myths of the Storm. Aztlan was reintroduced into the world as a way of becoming different. (He pauses…contemplating.) Our ancestors of Aztlan desired a new world.

Mama Teresita and her weeping women are leaving the mountains with lit torches. They are walking in the direction of the bonfire. It was beautiful to witness such acts of community, such collective grieving. Although people across the world were connected and shared a planetary sense of community, the Storm was not kind. People were contained by their territories. Some were forced or pulled into the Storm’s core, a geography once called the “United States of America,” a beast built by enslaved people whose architects were the white ghosts. This old, old place, once called a nation, is where Aztlan was first documented, somewhere in its lands. The second migration of many people toward the ancestral geographies of Aztlan was less about finding a territory but sharing life across a line the white ghosts called borders. This line was hundreds of miles long. This second migration was not always about a people’s desire to cross this border but a search for something else. This was something else that was hybrid. Work. Refuge. Exile. Displacement. Disaster. The list goes on.

Tata Gerardo: (Resuming his smoking, adding new dried leaves of tobacco and a hint of fresh rosemary, he feels a sense of dread as to where his story is going.) For the Chicanos, whom some of us descend from, Aztlan united the masses in ways unimagined from what came before; it was un chingo de gente. Yet, it also caused many problems. Aztlan was a story like many others, but it was not an agreed-upon prophecy. It created a spiritual bond between relatives across territories, languages, and cultures, but it was not always embraced. In fact, over time, it disappeared into the dreams of many, and new visions burst forth from new generations. (He takes a long breath.) Then, the collapse came.

Hormiga Victorino: Tata, if Aztlan disappears, then why tell a story about it? Is that all?

Hormiga Briana: My Nana says that the bad Chicanos disappeared too!

Hormiga Giselle: Well, my older brother said he once heard a story from a Yoeme medicine man that Chicanos went south a hundred years ago! Never found again.

Tata Gerardo: (Raising his hand to speak.) Children. Listen closely. Times are changing. I respect you too much to keep my mouth closed. I am telling this story because I am old, and I will not see another year if my sickness takes me. (He looks around, looking each hormiga in the eye, a sign of respect.) What I am about to tell you is heresy to the Council of Elders.

Tata Gerardo gets up from his seat and uses his bare hands to put wood into the bonfire. He takes out a medicine bag. From it, he brings out a dark yellow rock glued to wood. He tosses the copal into the bonfire. He sits back down with the help of hormiga Giselle.

Unbeknownst to the children, Tata Gerardo is a contrarian to the hormiguero of Tovaangar. He was asked to leave the Council of Elders a few years ago due to his strange visions and his persistent proposal that the autonomous territory prepare for a second Storm. His cries for self-defense were met with the reality that no white ghosts had been seen for over two decades, with scouting parties and nomadic hormigueros not being able to identify activity or a hint of mysterious movement. Tata Gerardo was of the old ways. His family had migrated north from P’urhépecha lands during the era of After the Storm. Some believed that his family’s fluency was due to middle-class experiences in the old world during the Storm. Others had rumors that he was a descendant of Chicanos who fled south. Very little was known about these Chicanos. The leading theory was that they escaped to multiple pueblos they built networks with during the Storm, integrating into the new lands they were welcomed to. Another theory was that they joined a rebel hormiguero in Maya lands. No one had answers.

It wasn’t by chance that Tata Gerardo was leading his clandestine circle. These children were familiar with his family and clan. Their parents were some of the few who advocated for him to stay a councilperson. Having been refused, these advocates shared a blemish on their name.

Mama Teresita’s cries could be heard louder. She is almost at the bonfire.

Hormiga Giselle: (Inquisitive, shy to even ask the question.) What is heresy, Tata? Why would the elders be mad at that? Will they be mad?

Tata Gerardo: That word is used for those who might say or do things that question the accepted truths of a people. None of you has ever heard of Aztlan, and there is a reason for that. Even in my telling of this story, I risk too much. (He lets out a sigh, deep from his diaphragm.) You see, children, there is a third Aztlan. It is the reason why we do not speak of its history. To utter its name is heresy.

Hormiga Briana: (Almost excited to be rebellious.) Tell us, Tata! We want to know!

Tata Gerardo: (Smiling but aware that what follows has consequences for the autonomous territory.) For two decades after the storm, the lands were partitioned by the dreams of what was called revolutionary separatism. This time was disastrous and difficult. Civil wars, capitalists on the run, people struggling for subsistence, and large territories in cities ruined by abandonment. Aztlan became a territory, large and wide, encompassing the lands we live on all the way to Kickapoo territory near the gulf. In the lands of the Gulf, to the eastern coast was the Republic of New Afrika. The rest was Indian Country. As the story goes, a woman refused the patriarchs of the nation of Aztlan. She was exiled along with her son. The son’s father desired to be in Aztlan with his son, and the mother refused. (He pauses.) She kills her son. The mother kills herself, too.

Hormiga Victorino: (Shocked.) Why…did she do that?

Tata Gerardo: There are many interpretations from those of us who remember. But you see, children. Those Chicanos who fled south were escaping the patriarchs and homophobia of Aztlan, in honor of Medea, the child-killer who was also a lesbian lover to another woman. The grief of the world, After the Storm, is heavy to bear. What the Council of Elders don’t want you to know is that Aztlan, this new and third movement, was abolished by the very same Chicanos who fled south and returned five years in the anniversary of Medea’s suicide and Chacmool, her son’s death. They envisioned another world and struggled against the authoritarians who would not give it up. It is the world we know today. Yet, with time, the Council of Elders has revised this history… (He looks to the fire.) They want nothing to do with it.

Mama Teresita: Lies! Heretic! Blasphemous words!

The weeping women scream it all together: Lies! Heretic! Blasphemous words! They are standing in the distance, near the bonfire. Despite their exhaustion, they are standing firmly, heads high, mascara streaming across their face.

Tata Gerardo stands up. He pulls in smoke and lets his lungs exhale. The children watch with anxiety and anticipation. The weeping women stand behind Mama Teresita as she points her long finger at Tata Gerardo. Her accusation is not without consequence.

Tata Gerardo: (A bit anxious but steadfast.) Mama Teresita, please, take a seat. Sit in my chair. As for the rest of you, I apologize, but there are blankets near Briana.

Mama Teresita: (With a sharp tongue, she pierces through the smoke.) Gerardo, you know that the words you speak are unfaithful. They are shameful words for children to hear. How dare you utter the name Medea. How dare you speak of Chacmool, that poor boy. Your blood is heavy. Your ancestors would be ashamed.

Tata Gerardo: (Cautious. He takes a piece of paper out from his pocket. An old paper. Burned.) Please, Mama Teresita, do not speak of my ancestors. I am full of grief for your boy, but I will not tolerate these accusations and staining of my name.

Hormiga Briana: (Reserved but daring.) Mama Teresita, why is what Tata shared heresy? Why speak to him like this? What lies has he told?

Mama Teresita: Children, please come with me. Let us go. You’ve heard enough. This conversation is not for you. (She reaches out her hands.).

Hormiga Giselle: I won’t go anywhere without Tata.

Hormiga Victorino: (Nodding his head.) Me neither.

Hormiga Briana: (Looking to her friends, then at Mama Teresita, and then to Tata Gerardo.) I don’t know what to do. (She starts to cry.).

Tata Gerardo: Children. Grieving mothers. Please. As your elder, I implore you to listen. I am not asking you to agree with my version of history or to defeat me without listening to what I have to say. Weeping women, I stand here with the most respect for you all. Antonio, poor Antonio. He was not meant to die such a young death. (He remembers being there, praying for Antonio, little Antonio, as they sewed his mouth, placed obsidian on his eyes, brushed his body, laid him to rest.) But hear me. The Council of Elders has been fusing too much power these last few years with their law. I know we know this. They fear that the autonomous territory will shake and tremble with the war we are waging against the white ghosts. They desire to create an authority that will command our territory. It is an understandable proposal, but it is not a proposal. They are imposing this on us. I had warned them years ago about a great violence that would come to our lands. They do not respect the old ways. They have learned much from the records we have, the white ghost archive. They abandoned our principles.

Weeping Woman María: Gerardo, you speak lies. Your words are heresy. You know the consequences.

Tata Gerardo: María, your father is on the council. Do you know what his last words to me were when I was publicly asked to leave the council? In passing, he told me, “And now the last Chicano is banished from our council.” Now, what does my being a descendant of Chicanos have to do with wanting me off the council? I am the last elder who carries the story of Aztlan. I carry the painful memory of Medea and those Chicanos who made Aztlan into a soulless authoritarian state. I know Aztlan is the key to our freedom. But it isn’t the version of After the Storm. It is why the council has campaigned against me, calling me a mad medicine man with bad visions and terrible politics. Do you know what I really think? (He enunciates every word, with the trembling of the earth.) We are lost souls. Just like those Chicanos who built Aztlan as a patriarchal nation. Our autonomy is a ruse. Our assemblies are led by an inner circle. Our children taught a history that is a revision of what is true. Mama Teresita, weeping women, please hear my words: We live a lie. That is the price of our autonomy.

The grieving mother, Mama Teresita, takes a seat in Tata Gerardo’s chair. She takes his offering of the pipe. She pulls in the tobacco. She releases it to the skies. The weeping women gathered around the bonfire, placing blankets down to sit.

Mama Teresita: (Contemplative, exhausted in the cold.) You know, Gerardo, your late partner Jéssica would have loved seeing you tell stories again with the children. (She pauses, finding her words.) Your heresy is true. Do not challenge the accusation. I am scared for the children. For us. For our people. Jéssica had already told me about these things, about the council and their moves for political power. (She takes another puff from the pipe.) But listen, Gerardo’s too much at stake here. We don’t need another Aztlan when we have each other. Poor Jéssica believed it too. She told us all. She died a heretic. Let us forget these dreams. Aztlan won’t bring back my Antonio.

Tata Gerardo: No. Aztlan won’t bring back your boy. That is true. (He sighs.) I am an old man with old dreams. Dreams like the Chicanos who thought they knew the path. (He looks at the paper he brought out.) This paper I hold in my hand is a manifesto or pamphlet from the old days, during the Storm. It is an old paper. Burned around parts. Hard to read. It was passed down to me from my grandmother. One day, I will give it to one of you hormigas, as we weather the new Storm before us. The legible part is only a couple of words. It reads…

It is my right to remember.